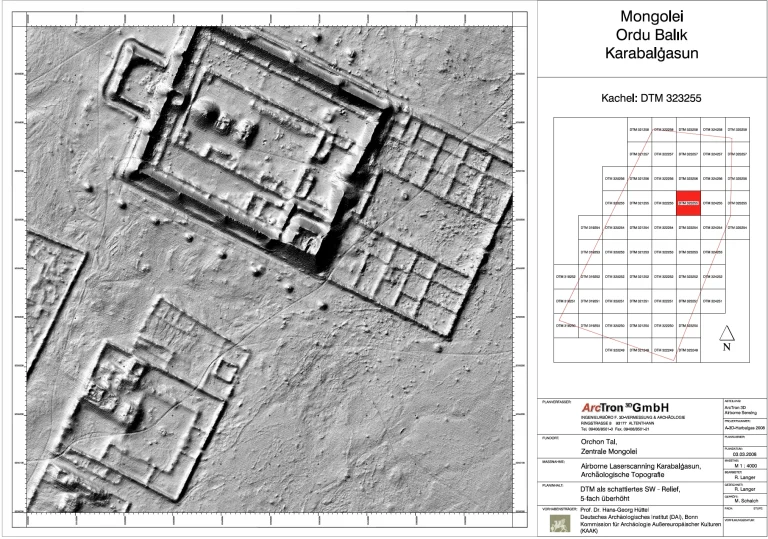

Karabalgasun Temple and Palace City

The most prominent area of Karabalgasun is probably the temple or palace city, whose towering walls are still visible from afar in the landscape. With an area of 390 x 460 m, it is considerable in size.

The Enclosing Wall

The remains of the enclosing wall still stand up to 10 m high and are well preserved on almost all sides. Despite weathering and erosion, the construction technique is still clearly recognizable. Following the Chinese model, the walls were built with rammed earth construction (Terre Pisé/Hangtu 夯土), which was stabilized at regular intervals by alternating diagonal horizontal tie beams. In visible areas that are more exposed to the weather, only cavities remain today; the timbers have long rotted away. The walls taper towards the top and are up to 35 m thick at the base. Bastion-like extensions at intervals of approx. 100 m also act to stabilize the construction and give it the extremely defensive appearance it is still known for today.

The Inner Complex

The so-called citadel is located in the south-eastern corner of the large rampart. It is again separated from the rest of the complex by higher walls and comprises an almost square, raised inner area (link to article Citadel). Numerous other inner walls divide the interior of the temple/palace city into regular areas and suggest that there were also buildings here. An excavation in the south-eastern inner area of the temple and palace city in 2023 provided more precise information on the building type for the first time. Large areas of lime screeds, divided by walls at right angles to each other, can be clearly interpreted as traces of past buildings. The walls were only preserved at their deepest points and were originally made of unfired clay bricks, which in turn was clad with wall plaster up to 25 cm high. Only in one corner was the wall reinforced with fired bricks and thus better preserved. The walls themselves had no load-bearing function; instead, the roof was supported by wooden pillars standing on stone bases. These column bases were made of roughly cut square granite segments, and were set below the screed that partially passes over them. Only small charcoal remains had survived from the rising timber construction. Two column bases were uncovered beneath the walls, while two others were probed but not uncovered. One of these, one was located in the corner of the recorded wall, and the other was found asymmetrically in the east-west running wall with reference to a very narrow partition wall branching off to the north. The wooden studs were integrated into the walls and acted as support, so that they could simply be erected in mud bricks. In the eastern part of the excavation, no wall was preserved between the column bases; there may have been a doorway here.

Excavations within the Temple and Palace City

Possible Subsequent use at a Later Date

In summary, it can be assumed on the basis of these excavation findings that these simple construction casemate-like buildings would have stood along the enclosure wall within the temple/palace city, and fulfilled a variety of functions. In his description of the city, Rubruk mentions a large residence, in the entrance area of which a tree made of silver and richly decorated served as a bar for five different drinks. According to his description, the palace itself had three naves with three portals facing south. Inside, the ruler’s throne was located on the north side, while the women of the court were placed on the east side and the men on the west side. This spatial arrangement corresponds to that which is also common in Mongolian yurts today.