The Orkhon Valley

The Orkhon Valley is a UNESCO World Heritage Site both for its global historical significance and for its rich cultural landscape. For thousands of years it has been home to nomads and was repeatedly the centre of great empires that had a decisive influence on the history of the Eurasian continent.

Panoramic View of the Orkhon Valley

Natural Conditions

Karakorum and the Orkhon Valley are located at the edge of the Changaj Mountains in the center of present-day Mongolia. Geologically, the Orkhon Valley is diverse. Rocks from the Paleozoic era, some 570 to 225 million years ago, were broken up by tectonic processes and folded and uplifted to form a mountain range. During the Pleistocene, the Ice Age, the landscape was further shaped by glaciation and the melting of glaciers, but also by volcanism. The upper Orkhon Valley in particular displays impressive black basalt formations that can be traced back to this phase. The name Kara-Korum probably also goes back to the Old Turkic and Mongolian “qar” – black and “qorum” – scree, stone. Since the end of the Ice Age, the landscape has been shaped by climate change and erosion by the elements.

Over the last 11,500 years or so, phases of a wetter climate with extensive forests and drier phases with an expansion of steppe areas have alternated. The Orkhon and its tributaries meander through this landscape, constantly changing their course and depositing material from the upper regions of the mountains. Over time, fertile floodplain soils formed in the area around Karakorum, which could be successfully used for agriculture and are still used today.

The Valley

The Orkhon and its tributaries meander through this landscape, constantly changing their course and depositing material from the upper regions of the mountains. As a result, fertile alluvial soils formed in the Karakorum region over the course of time, which were successfully used for agriculture and are still used today. At the time of the Mongol Empire, in the 13th century, the landscape was probably much wetter and more forested than it is today. In the Orkhon valley there was an alluvial forest with typical trees such as elms and willows. The neighbouring ridges of the Changaj may also have had a denser larch forest than today. The construction of a town and the associated enormous demand for building and firewood led to a significant reduction in forest areas even then.

Essential Resources

It was certainly also the fertile soils and pastures of the Orchon Valley that led to the decision to establish the centre of the empire right here. There was enough pastureland and sufficient water to gather large herds. This fulfilled one of the basic requirements for holding political events such as aristocratic gatherings or preparing campaigns in a nomadic kingdom. In addition, the fertile pastures ensured a permanent supply of meat and fat for the urban population. Annual ring data prove that, especially at the time of the expansion of the Mongol Empire and the founding of Karakorum, climatically favourable conditions with relatively high temperatures and high precipitation favoured the region and thus created ideal conditions for the founding of the city.

Settlement up to the Iron Age

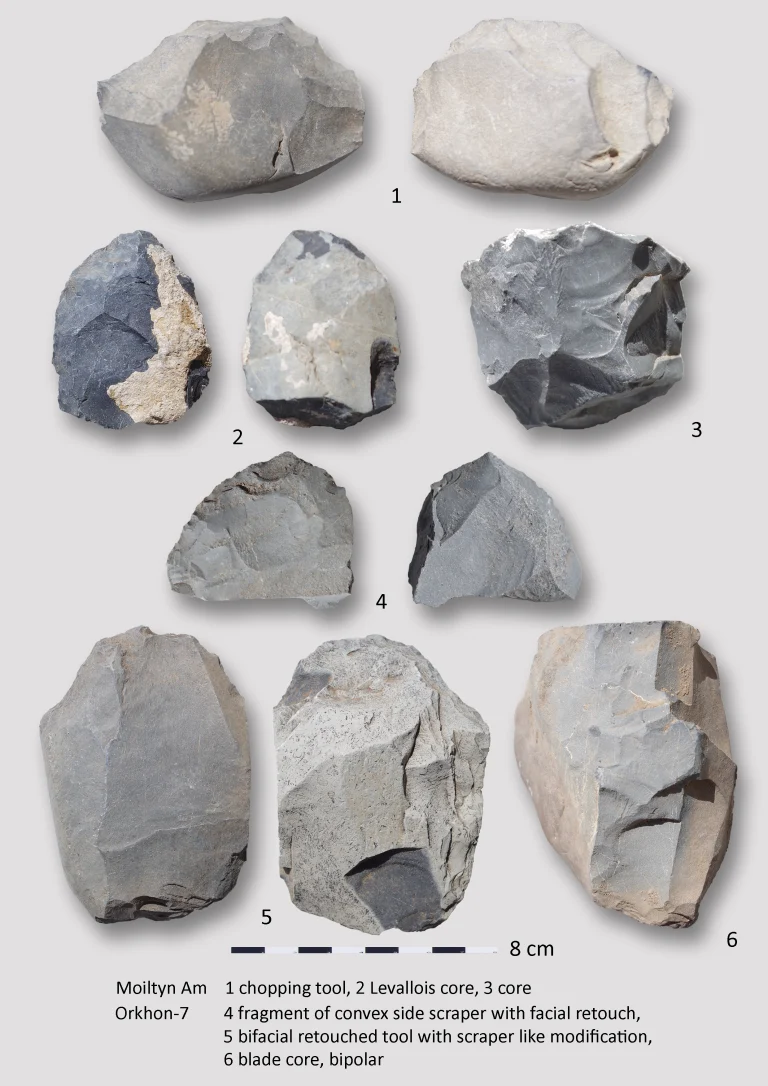

The history of this world-historical place does not begin in 1220. The choice of the wide valley of the Orkhon as the site of the Mongolian capital goes back thousands of years. Even Palaeolithic hunters sought out the valley. On a river terrace just four kilometres northwest of the Erdene Zuu monastery, at the entrance to the valley called “Moiltyn am”, there is an extraordinary Stone Age site. From this place, you can see the wide Orkhon valley, but it is still sheltered by the foothills. This favourable location, but also the availability of high-quality stone material, led to this place being visited and inhabited by people again and again over many millennia. As early as 1949, a Mongolian-Soviet expedition discovered stone tools from various eras here. Between 1960 and 1965, several thousand stone tools dating from the Late Palaeolithic (approx. 40,000 to 15,000 BCE), the Middle (15,00 0 to 8,000 BCE) and the Neolithic (8,000 to 3,000 BCE), including axes, knives, blades, scrapers, awls and arrowheads. Numerous stone chips testify to the manufacture of these tools at this site.

A little further upriver, in 1986, archaeologists from a Mongolian-Soviet expedition found a second site from the middle and late Palaeolithic period, which became known as Orkhon 7. Analyses of plant remains from the excavated layers showed that the climate of the region was wetter and milder during this period, resulting in a great variety of grasses and deciduous forests in the valleys. Since 2018, a Russian-Mongolian expedition has been conducting research on site. Since the late Bronze Age (1400–750 BCE) and early Iron Age (750–250 BCE), nomadic people have settled in what is now Mongolia. They lived from livestock farming and hunting, but also from trade and specialized crafts. In order to use the resources offered by the steppe efficiently, people had to travel great distances. The cattle had to be driven regularly to fresh pastures and to suitable water sources to prevent the natural resources from being depleted too quickly. One of the most significant innovations in human history helped to solve this problem: riding. Travel on horseback made people mobile and allowed them to practice a completely new type of pastoral farming, enabled new hunting techniques and long-distance communication. The culture of mounted pastoralism or equestrian nomadism emerged, as it is still practiced to some extent in Mongolia today.

Burial Grounds

Many monuments along the Orkhon Valley still bear witness to the time of the early nomads in Mongolia. In particular, the upper reaches of the Orkhon are lined with countless graves, deer stones and other monuments from the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Numerous so-called “Khirigsuur” can be found here, for example. These are monumental tombs, usually with a stone mound in the middle, surrounded by a circular or square enclosure. There may be many other structures such as small, round stone settings. Some archaeologists interpret these stone settings as sacrificial offerings; they often contain animal bones or even bronze artifacts. Hundreds of these small cairns can be found around some large khirigsuurs. These sites bear witness to a profound change in Bronze Age society: in the earlier periods, such prominent graves are rare. The large amount of work involved in their construction and the fact that they were visited and venerated over long periods, perhaps over centuries, indicate that during this time, individual persons were able to accumulate a great deal of power and prestige, and that society was increasingly hierarchical.

Stag Stones

Another fascinating type of monument from the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age are the so-called stag stones. These are originally upright stone steles that depict highly stylized people or warriors. Details such as the head, torso, and belt with weapons are often depicted in an abstract way. The most characteristic feature, however, are the rows of stylized deer jumping diagonally upwards in the area of the torso. The exact function of these stones is not clear. Small pits or stone settings with offerings are often found next to the deer stones. Since they obviously depict warriors, they could also have been memorial stones or guardian figures. These monuments are spread over a large geographical area from Mongolia to Xinjiang and Kazakhstan to the Black Sea region. They bear witness to the extensive cultural exchange that the mounted nomads practiced as early as the 1st millennium BC. Some examples can be seen at the “Temeen Chuluu” cemetery in the upper Orkhon Valley.

Slab Graves

The third characteristic legacy of the early equestrian nomads are the so-called slab graves. The slab graves were built with a rectangular enclosure made of upright stones, inside of which there is a dense layer of stones on the floor. There are both small examples, with sides about two to three meters long, and monumental structures with sides up to more than ten meters long. The monuments of this period bear witness to the social differentiation that went hand in hand with the development of pastoral nomadism and the introduction of metallurgy. Traces of this exciting era can be found scattered throughout the landscape around Karakorum. Bronze Age tombs are particularly dense in the upper reaches of the Orkhon, especially in the Chujirt and Bat-Ölzij Sum. But the attentive observer can also find stone-piled tombs from this era in the middle Orkhon Valley, along the road to Khotont.

The Orchon Valley as the Cradle of the Nomadic Empires

The first historically recorded empire to be established by the equestrian nomads of the Mongolian steppes was that of the Asian Huns or Xiongnu. Most of what we know about them today comes from the records of Chinese chroniclers. China, which at that time for the first time represented a unified state under the Han Dynasty, maintained close and diverse relations with the Xiongnu Empire. On the one hand, the steppe peoples were important trading partners for the acquisition of luxury goods such as furs from the north; they also supplied the horses for the development of a powerful cavalry and bought agricultural products and luxury goods such as silk from China. On the other hand, they posed a serious military threat, which repeatedly manifested itself in raids on garrisons and towns near the border and corresponding retaliatory campaigns. Despite their numerical inferiority, the horsemen from the steppes were a dangerous opponent for the cumbersome Chinese infantry levies. After all, they had been trained in horse riding and hunting with a bow since childhood. This tactical superiority occasionally allowed the Xiongnu ruler, the Shan-yu, to bring the Han Empire to a state of virtual tribute dependency. These intensive relations led Chinese scholars to study their neighbours, the “northern barbarians.” The most important Chinese source on the Xiongnu is Sima Qian’s Shiji. This historical work contains not only information about the history, but also the customs, traditions, way of life, economy and military skills of the Xiongnu. His comments are characteristic of the view of settled cultures on the nomads of the steppe:

“Their livestock consists mainly of horses, cattle and sheep. […] They wander back and forth, seeking water and plants. They have no walled cities or permanent residences, nor do they cultivate the land, but each person still owns a piece of the soil. They have no writing. Agreements are made orally. Children can ride on mutton or sheep, stretch a bow and shoot birds, weasels and rats; when they grow up, they shoot foxes and hares for food.”

Early Nomadic Empires

The Xiongnu empire existed from about 209 BCE to 93 CE. After the end of the Hun empire, powerful empires such as that of the Xianbei in the 2nd and 3rd centuries and the Rouran in the 4th to 6th centuries repeatedly ruled the steppe. We do not know exactly what role the landscape of the Orkhon Valley played for these early nomadic empires.

As early as 1924, the Austrian sinologist Arthur von Rosthorn pointed out in an article that the regions between the Changai and Sajan mountain ranges, along the Orkhon and Tuul rivers, were the retreat areas and power centres of the nomadic empires. He derived this insight from Chinese reports of military campaigns in the region. Chinese generals who wanted to defeat the Xiongnu invaded precisely this region. So the main camp of the Hunnic ruler must have been here.

The Old Turk Empires

Reliable information about the special significance of the landscape along the Orkhon River first reaches us from the early Middle Ages, the time of the Old Turk or Gök-Turkic empires, which established themselves in the territory of present-day Mongolia under the leadership of their rulers from the Ashina clan from the mid-6th century. After the Turkic Empire split into an eastern and a western half, the Eastern Turkic Empire in particular achieved a political supremacy. Its center was the “Ötukan”, the region near the Changaj Mountains, which was attributed a special religious and social significance. After various political upheavals, the first Turkic Empire came under the control of the Chinese state in the middle of the 7th century. At the end of the 7th century, however, Kutlug, a ruler from the Ashina clan, managed to break away from China again and establish the Second Turkic Empire within its old borders. Numerous figural stone steles in the Orkhon Valley bear witness to the time of the Turkic empires and can still be seen today.

Köl Tegin Stele

From this period, we have Chinese, Central Asian and even Byzantine written sources, which portraited the Turks from the external perspective of a foreign people. Now, for the first time, independent written sources from the Old Turks themselves show the steppe nomads’ own view of the political and historical events. The most important Old Turk text documents are large stone steles with detailed inscriptions. They were erected in memory of rulers and high dignitaries. These inscribed stones usually not only report on the deeds of the ruler or dignitary, but also contain historical treatises and political advice for posterity. They provide us with interesting insights into the political and ideological inner workings of a great nomadic empire. The outstanding importance of the Orkhon region is emphasized on several of these steles. On the inscription stele of Köl Tegin in the Turkic memorial complex Khöshöö Tsaidam, which has been preserved to this day, it says in Old Turkic runic script:

“If you stay in the land of Ötukan and send caravans from here, you will have no difficulties (Turkic people!), if you stay in the Ötükän mountains, you will live forever and rule the tribes!”

Tonjuk Memorial Stone

On the memorial stone of Tonjukuk, an outstanding statesman of the second Old Turk Empire, near the modern capital Ulaanbaatar, which has also been preserved, it reads: “When they heard the news that the Türks had settled in the land of the Ötükän, all the peoples who lived in the south, west, north and east came.”

(Translation by Scharlipp, Wolfgang Ekkehard. Die frühen Türken in Zentralasien: Eine Einführung in ihre Geschichte und Kultur. Darmstadt 1992, 35 [The early Turks in Central Asia: An introduction to their history and culture.])

From these texts, the special significance of the Orkhon region is clear. It was regarded as a kind of sacred heartland, as an indispensable centre of an empire in the steppes.

The Uighur Empire

When the Second Turkic Empire came to an end in 740, the Uighurs took control of the banks of the Orkhon. This Turkic people also established a steppe empire that extended far beyond the borders of present-day Mongolia. In the valley of the Orkhon, a large urban area was built for the first time, which served as a veritable capital. This city was the first large city complex with numerous buildings, including temples and palaces, to be built in the steppe along the Orkhon. The Uighurs called the city “Ordu Baliq”, the city of the military camp, today it is known as Karabalgasun.

The Khitan Empire

The Khitans are first mentioned in Chinese sources in 406. They probably spoke a precursor of the Mongolian language and emerged from a split in the Xianbei tribal federation. They lived on the eastern side of the Hinggan Mountains, east of the border between present-day Mongolia and Inner Mongolia. After the fall of the Uighur Empire in 840 and the decline of the Chinese Tang Dynasty, a power vacuum had emerged in East Asia. This allowed the Khitans, under their ruler Yelü Abaoji, to quickly build a large empire. From 907 onwards, he established a dynasty and took the name Taizu. With a capital modeled on the Chinese example, he demonstrated his claim to power. In addition to its core areas, the Khitan Empire ruled parts of northern China and Mongolia. In 924, Yelü Abaoji undertook a campaign in Mongolia and also visited Karabalgasun, ordering a new inscription to be made on a stele standing here. This shows that the Khitan rulers also saw an outstanding significance in this place and included it in their political and symbolic actions. Nevertheless, the Orkhon Valley was probably not a center of this empire during this period. Archaeological traces from this epoch are correspondingly rare. Nevertheless, during the excavations in Karabalgasun, remains were found that may indicate that the site was used during the Khitan period.

The Mongol Empire

The rulers of the Mongol Empire were undoubtedly aware of the historical and symbolic significance of the Orkhon Valley. It was certainly no coincidence that in 1220 they founded one of their main camps and the most important city of the young empire right here in Karakorum. During this time, the Orkhon Valley reached the zenith of its global historical significance. Together with Karakorum, it became the center of an empire that comprised most of the then-known world. The Old Mongolian capital became a center of attraction for legations and merchants from all over the world and a starting point for major military campaigns. After the complete conquest of China and the founding of the Yuan Dynasty by Kublai Khan, the capital was moved to Dadu, present-day Beijing. Nevertheless, Karakorum remained an important center where the memory of the origin of the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty was cultivated. After the end of the rule over China in 1368, Karakorum once again became the center of the dynasty, which retreated to the Mongolian heartlands. In addition to the ruins of Karakorum, there are numerous other archaeological sites from the time of the Mongol Empire in the Orkhon Valley. Further north, for example, are the ruins of Doytijn Balgas. This was a residence of Ögedej Khan, known to us from written sources, and was probably built by craftsmen from Muslim Central Asia. In times of peace, the monoglic rulers used to spend the summer here, hunting waterfowl on the surrounding lakes.

The Modern Era

After the end of the Yuan Dynasty, the Orkhon Valley remained a spiritual center of Mongolia. Abtai Sain Khan built the Erdene Zuu monastery on the ruins of the old capital in 1585. It is the oldest preserved Buddhist monastery in Outer Mongolia and a center for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings among the Mongols.

In 1939, the monastery was severely damaged as a result of political persecution. The main temples, however, were spared and still bear witness to the millennia-long history of the Orkhon Valley as a spiritual center of the nomadic states of the Mongolian plateau.