Discovery of the Falcon Skeleton

In order to investigate the question of the walking level in the courtyard of the citadel, a trench was made in the courtyard, but the pavement showed disturbances that were investigated by excavation and the well was discovered. An almost complete bird skeleton, several fragments of vessels and pieces of granite stone were found in the upper part of the disturbance.

Intentional Deposition

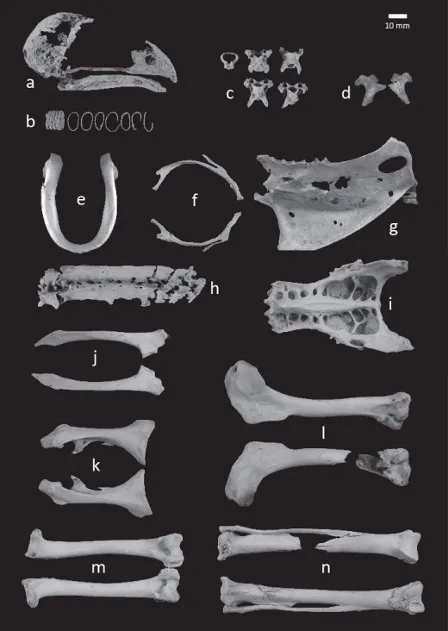

The arrangement and position of these artefacts suggested that they had been deliberately placed, perhaps in a ritual context, a suggestion that was also supported by closer examination of the bird’s skeleton. Scientists from the Museum König in Bonn, Germany, discovered that we had found large parts of the skeleton of a gerfalcon, a species of falcon that is not endemic to Mongolia. The falcon’s carcass was missing the wings, including the primary and secondary flight feathers, the tail and the clawed feet. Some of the rib bones show signs of older, healed fractures with clearly visible bone calluses. These fractures would not have healed in the wild. The healed fractures of some of the falcon’s vertebral ribs indicate a severe, but not fatal, injury to the chest, which would likely have required a longer recovery period in captivity. These injuries may have been caused by a collision or violent encounter with another raptor or mammal. What is certain is that the bird was unable to move sufficiently while the injuries healed and was unable to hunt. At the same time, the still visible healing of the bones indicates that the injured raptor was nursed back to health in captivity.

Analysing the bones

As the healed rib fractures were obviously not the cause of death of the Karabalgasun falcon, it is likely that the recovery took place under human care, i.e. the bird was kept (and fed) in captivity. It is known that nomadic peoples had a complex knowledge of keeping and caring for birds of prey, especially in the context of falconry. At the same time, these birds were a respected symbol of status and wealth, so we assume that the Karabalgasun falcon arrived in Karabalgasun as a trade item or gift from a neighbouring ruler in the northern regions and was probably kept there for hunting purposes. The age of the bones, determined by radiocarbon dating, suggests the proto-Mongolian Kitan period, which also suggests that the ruins of the ancient Uighur capital were still important some 100 years after its destruction.

Further animal bones

In addition to the falcon’s skeleton, the excavation of the citadel unearthed a number of other animal bones that provide clues to the Uighur diet and the use of animals in the Uighur Empire. Based on the findings, it can be said that sheep and goats were the most commonly used animals, followed by horses and then cattle. Slaughter marks still visible on the bones of the animals also allow us to determine the exact age at which the animals were slaughtered. Despite the adoption of Manichaeism, a religion that is supposed to abstain from meat, the diet of the Uighur elite seems to have remained closely linked to the nomadic traditions of the steppe.