The Great Hall

The site we now refer to as the Great Hall is associated with some of the most exciting finds and the most intense controversies surrounding ancient Karakoram. It is located at the southwest corner of the city, where a large platform rises above the surrounding area.

Where was the Palace of Ögedei Khan Located?

In front of this pedestal, which is now accessible as an open-air museum, there is still a large stone turtle. An inscription stele was once embedded in its back shell, presumably the inscription from 1346. Various researchers have been collecting its parts scattered around the city since the 19th century. The question of where exactly the palace built by Ögedei Khan was located has long been debated. Rubruk wrote:

“Not far from the city wall of Karakorum, Mangu [Möngke Khan, the author] owns a large palace surrounded by a brick wall, like the monasteries here. There rises a large castle […]”

This passage seemed to apply exactly to the complex at the south-west corner of the city. It is located on the edge of the city near the city wall, was surrounded by a wall and contains a large building in the middle. Based on this match, the first archaeologist to work in Karakorum, Dimtirij Demjanovič Bukinič, suspected as early as 1933 that the complex in the south-west of the city could have been Ögedei’s palace. Kiselev later followed him in this opinion, although he found large quantities of terracotta that were more suited to a Buddhist temple than a palace. Throughout the 20th century, experts remained convinced that this ruin must be the remains of Ögedei’s palace. Only Mongolian-German research since 2000 shed new light on the remains.

The Excavations at the Great Hall

The team from the German Archaeological Institute, led by Hans-Georg Hüttel, began excavations at the presumed palace district in the southwest of Karakorum in 2000. Initially, a kiln district was excavated. Building materials for the construction of one or more large buildings were produced here. In addition, the Mongolian and German archaeologists began to uncover the still visible excavation sections of the Russian investigations of the 1940s on the large central building of the complex. This allowed them to gain an initial insight into the structure of the archaeological layers of earth and the existing building remains without touching the valuable, preserved original substance.

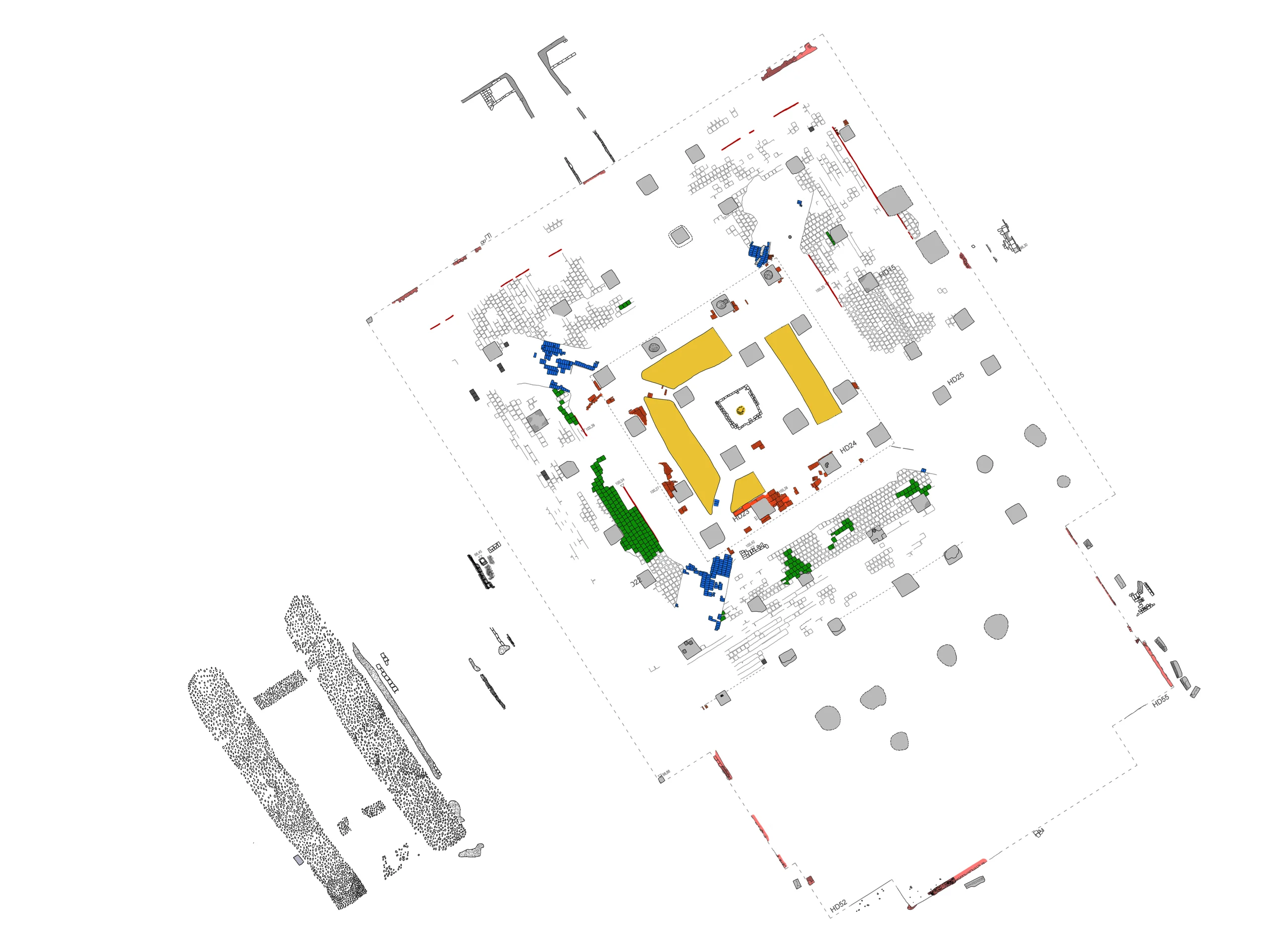

Panorama der Großen Halle

Floor Plan of the Great Hall and the Outbuilding

Blessing of the Building Through Offerings

In the centre of the quadrangle, exactly at the imaginary intersection of the diagonal entrances, the archaeologists discovered a large, grey clay jug containing grain remains inside. This jar had probably been placed here as an offering during construction to bring blessings and good fortune to the building. These offerings and remains of the wall were probably the remains of a large stupa, a Buddhist cult monument, which served as a central sanctuary here. Deposited vessels were also found below the outer corners of the podium and under the eastern and western stairs. They contained a large quantity of millet grains and a collection of offerings wrapped in cloth. They contained gold and silver coins, coral, pearls, turquoise, lapis lazuli, shells and objects made of wood, copper and steel. These form the group of the so-called “Nine Treasures”, which still have a deep spiritual significance in Mongolia today and, sewn into small bags, are worn by some as amulets.

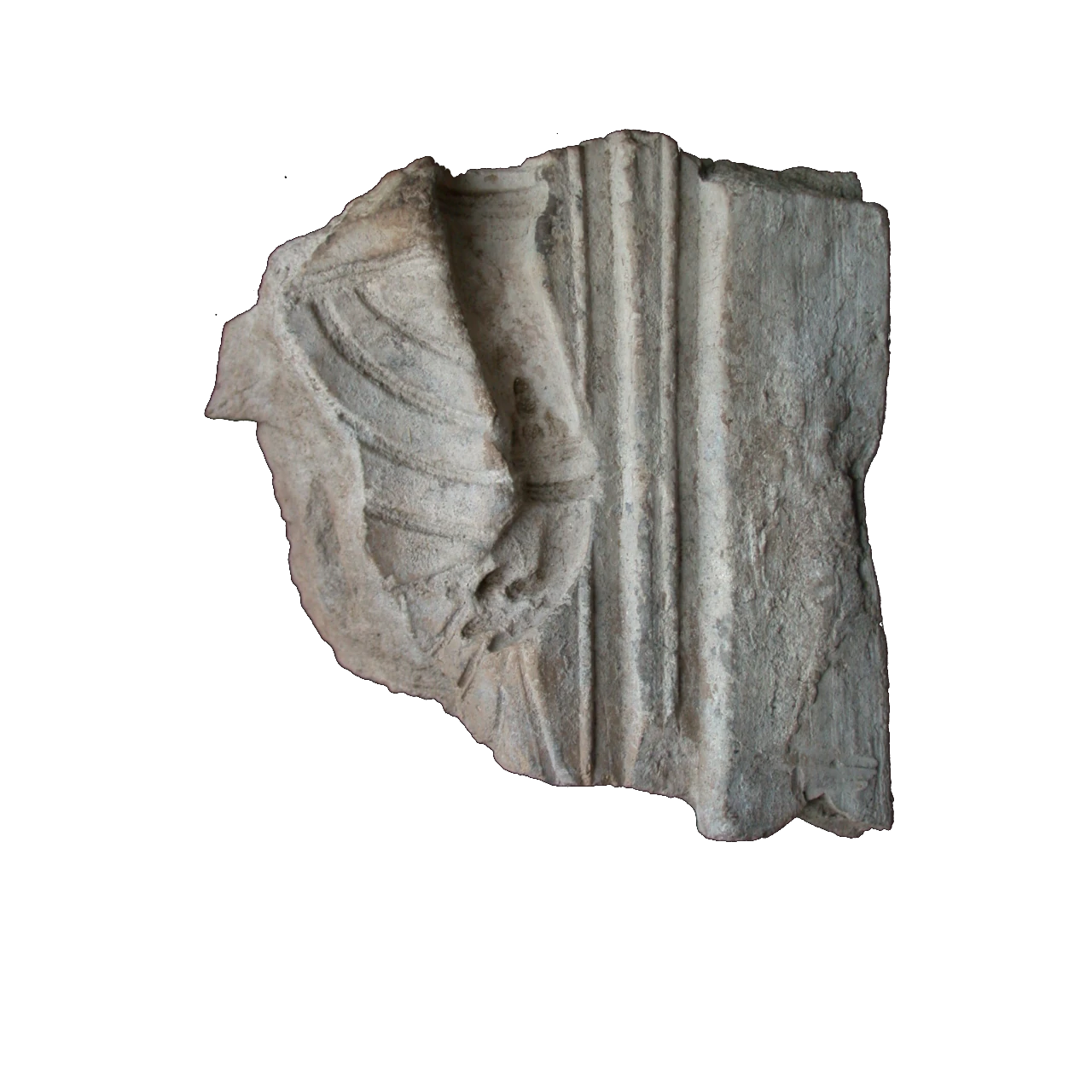

Objects Found in the Great Hall

Large cuboid granite blocks with sides more than a meter long were set into the surface of the podium. They served as column bases for the mighty wooden pillars of the multi-storey hall. Remains of the wooden pillar constructions were preserved in some places. They had a diameter of 80 centimetres and were surrounded by four wooden pillars, each with a side length of around 20 centimetres, creating a whole bundle of columns. rnrnIn total, the building was supported by 64 pillars placed at regular intervals. Hardly any of the timbers had survived. Only a few charred remains indicated the locations of the pillars. The building had therefore been destroyed by fire. This is indicated not only by the burnt timbers but also by the thick layers of rubble that the archaeologists had to remove. They contained many bricks and roof tiles, often deformed by fire and with a blistered, glass-like surface. In addition, fragments of sculptures, wall and roof decorations repeatedly came to light during the excavations. All these finds make it clear that this building is not a palace in the sense of a residence, but rather a large Buddhist temple, probably even the “Pavilion of the Rise of the Yuan Dynasty”, which is immortalized on the inscription from 1346 found in Karakorum.

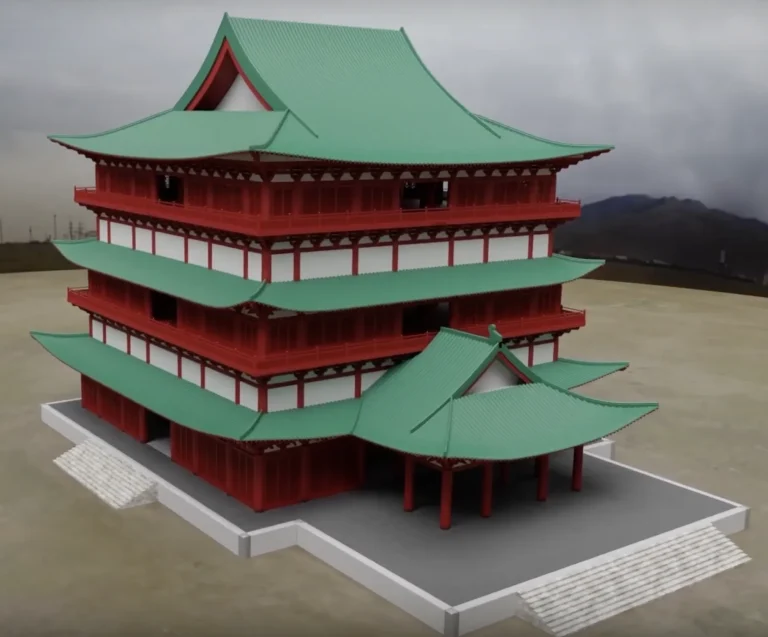

The Resurrection of the “Palace of the Rise of the Yuan”

Together, the remains found – the pedestal, the column bases, the paved floor, the layers of rubble on top and the finds – allow an approximate reconstruction of the building. The podium with the regularly arranged column bases, the roof tiles and the building decoration show that the building was modelled on Chinese temples. The traditional Chinese half-timbered construction method was used, which was also suitable for the construction of very large temples and palaces. Individual finds show that the construction was painted. Decorations in green, white and yellow were applied to a red background. The roof of the building was richly decorated with glazed tiles. Fortunately, the bilingual inscription from 1346 found in Karakorum also provides details of the structural features of the Great Temple of Karakorum. The better preserved Chinese text reads:

“[…] In the year bing cheng of the calendar cycle (1256), he [Möngke Khan] erected a large stupa and surrounded it with a high pavilion. […] The pavilion had five storeys. It was 300 chi [about 90 meters] high. As for the first floor, each side formed a room seven bays in size. In it they placed the statues of various Buddhas, in accordance with the sutras.”

The inscription dating the construction of the temple to the reign of Möngke Khan (1251-1260) is also confirmed by the finds. The most recent coins, which were deposited in the vessels at the corners of the building, bore his tamga, a kind of personal seal derived from the branding marks of herd animals. The coins were minted around 1254. As the vessels containing the coins were buried in the foundations, the temple could not have been built any earlier. For the year 1311, the inscription records that Buyantu Khan invested a lot of money in renovating the temple. In 1342, another extensive renovation was carried out under Togoon Temür Khan:

“[…] They painted gold around the stupa. Its brilliance dazzled the eye. As for the pavilion, inside and outside, above and below, in all its size, in all its twists and turns as well as in its carvings, lacquerings and whitewash, there was nothing that was not solid and beautiful, fine and perfect. They doubled its gates threefold and surrounded it with a closed wall. It was radiantly new.”

The large central building was surrounded by two smaller buildings on the west and east sides, a small north building and a gatehouse on the south side. The entire ensemble was closed to the outside and surrounded by a wall. One of the western outbuildings was also examined archaeologically. Thick layers of foundations made of coarse river boulders, which presumably supported a combined rammed earth and timber construction, had been preserved. Finds of roof tiles also clearly indicate that these buildings were also erected in the Chinese building tradition.

Finds from the Great Hall in the Finds Catalogue