The Research History of Karakorum

The archaeological and historical exploration of the city of Karakorum has a long history. While the significance of the ruins near the Erdene Zuu monastery has never been completely forgotten in Mongolian historiography, European scholars have long puzzled over the location and history of the city.

In Search of the Lost City

As Karakorum was briefly the center of the Mongolian Empire in the Middle Ages, it was mentioned in numerous medieval written sources, for example in Marco Polo’s travelogue. Even in the Middle Ages, the city was recorded on the maps of various cultures according to travelers’ reports. For example, the city first appeared on a European map in the Catalan Atlas of 1375. Karakorum is also mentioned on Chinese maps from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Nevertheless, the exact location of the city after its destruction was unknown except to some Mongolian scholars. Jesuit missionaries such as Matteo Ricci, Johann Adam Schall von Bell and Ferdinand Verbiest gained high positions at the court of the Ming and Manchu emperors and enjoyed the trust of the rulers. From the 17th century onwards, the Manchu Qing dynasty ruled China, Tibet, East Turkestan and Mongolia. This made it possible for missionaries to obtain information about these regions. In the 18th century, an atlas of the Qing Empire was published, which also included the Erdene Zuu Monastery and the ruins of Karabalgasun. In 1739, the Jesuit missionary and historian Antoine Gaubil published a history of the Mongol rulers from Genghis Khan to the end of the Yuan dynasty, based on his translation of Chinese sources. The exact location of the historical Karakorum has been the subject of repeated speculation. Gaubil already suspected the city to be in the region east of the Khangai Mountains.

The Ruins of Karakorum

In 1824, the French doctor, sinologist and librarian Jean-Pierre-Abel Rémusat attempted to localize Karakorum more precisely by studying Chinese written sources. He established a connection with the nearby Karabalgasun and correctly assumed that the city was already located on the Orkhon River. Just five years later, the work of the Russian monk Iakinf, whose real name was Nikita Jakovlevič Bičurin, was published. He also referred to Chinese chronicles and located Karakorum in the correct region. In a footnote, he indicated the location of the city on the eastern side of the Changaj Mountains between the Orkhon and Tamir rivers. Finally, in 1883, the Russian Mongolist Aleksej Matveevič Pozdneev identified Karakorum with the city ruins next to the Erdene zuu monastery. However, this was only a “discovery” from a European perspective. Mongolian scholars in the 19th century were aware of the connection between Erdene zuu and the Mongol rulers of the Middle Ages from their own historical works. Pozdneev took this information from the Mongolian chronicle “Erdeny-yin erike”, which was translated into Russian.

Monastery Foundations

The chronicle was written in 1841 by a high official of the Tusheet Chan Ajmag, Galdan Tuslagč. In the section on the founding of the Erdene zuu monastery, it says:

“In the year of the blue chicken, he [Abadai Khan] established a jandar at the ancient ruins called Tachai, north of the mountain Shanchat uul called Sharga azarga, where Ögedei Khan had previously resided in the year of the Fire Dog (1229) and which Togoontömör had later rebuilt, and founded the sanctuary known as Erdene zuu. He kept the relic of Shakyamuni donated by the Dalai Lama here, crowned it with a ruby and had the Gomin Nansu-goor perform the consecration. When the Dalai Lama himself announced that he was taking part in the ritual from afar, it rained barley grains as a sign. Since then, Erdene Zuu has been known as the sanctuary of Chalcha.”

Older chronicles such as the “Altan debter” also suggest a connection between Erdene Zuu and an ancestral sacrificial site in honour of the Genghisids. The Erdene Zuu monastery was therefore deliberately founded at this location in order to maintain the connection with Genghis Khan’s legacy. For a long time, Erdene Zuu was to remain the most important religious centre of outer Mongolia. Today it is the oldest surviving Buddhist monastery in Mongolia.

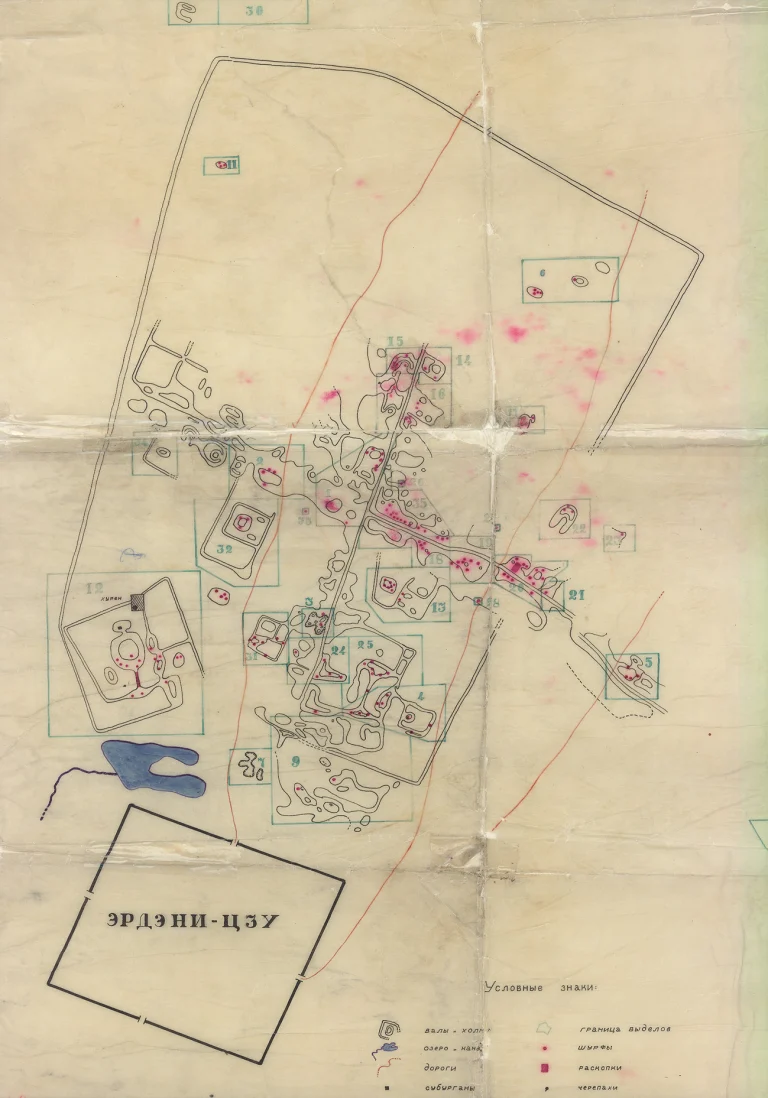

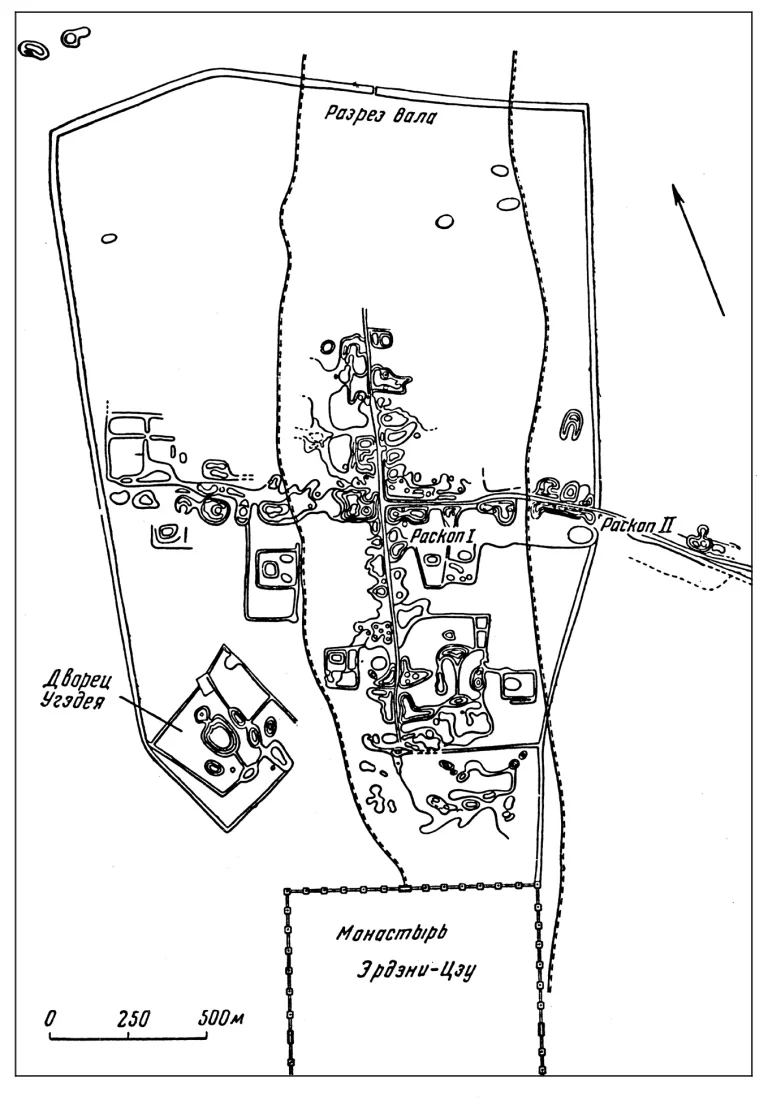

1976 – 1989 Graves and Chance Finds

Since 1976, an expedition led by N. Ser-Odcav, D. Bayar, D. Tsevendorj and G. Menes has been researching further questions relating to the archaeology and history of Karakorum. The aim of this expedition was to further refine the knowledge about the exact appearance of Karakorum and also to examine burials in the wider surroundings of the city more closely. The discovery of a cemetery with at least 37 burials according to Muslim rites in the north-western corner of the city is certainly one of the most important discoveries and confirms the existing image of a cosmopolitan city with great religious diversity. Due to the increasingly intensive agricultural use of the neighbouring state farm and the expansion of the neighbouring Harhorin sum centre, various chance finds were made in the 1970s and 1980s, including, for example, a supposedly complete chain mail shirt. These chance finds also include two African ruler portraits made of stone. They were found during construction work in 1975 and are still among the most unusual finds today. Their exact origin is still unknown.