The Excavation in the North City

On the northern outskirts of Karakorum near the North Gate, a prominent structure consisting of several mounds that is still visible in the terrain today was also examined more closely in 2007-2009. It is very likely that a small Christian church stood here, far from the centre of the city.

The Northern Outskirts of the City – a Place of Strangers?

So while the city centre appeared to be a Chinese-dominated craftsmen’s quarter, the expedition searched for traces of the other cultures present in Karakorum. Where were the Muslim traders, where were the Christians and other foreigners? The court and its entourage resided in the south of the city and the city centre was inhabited by craftsmen. This left only the outskirts of the city in the north and east as places of foreigners, traders, guests and minorities.

The Northern Outbuilding

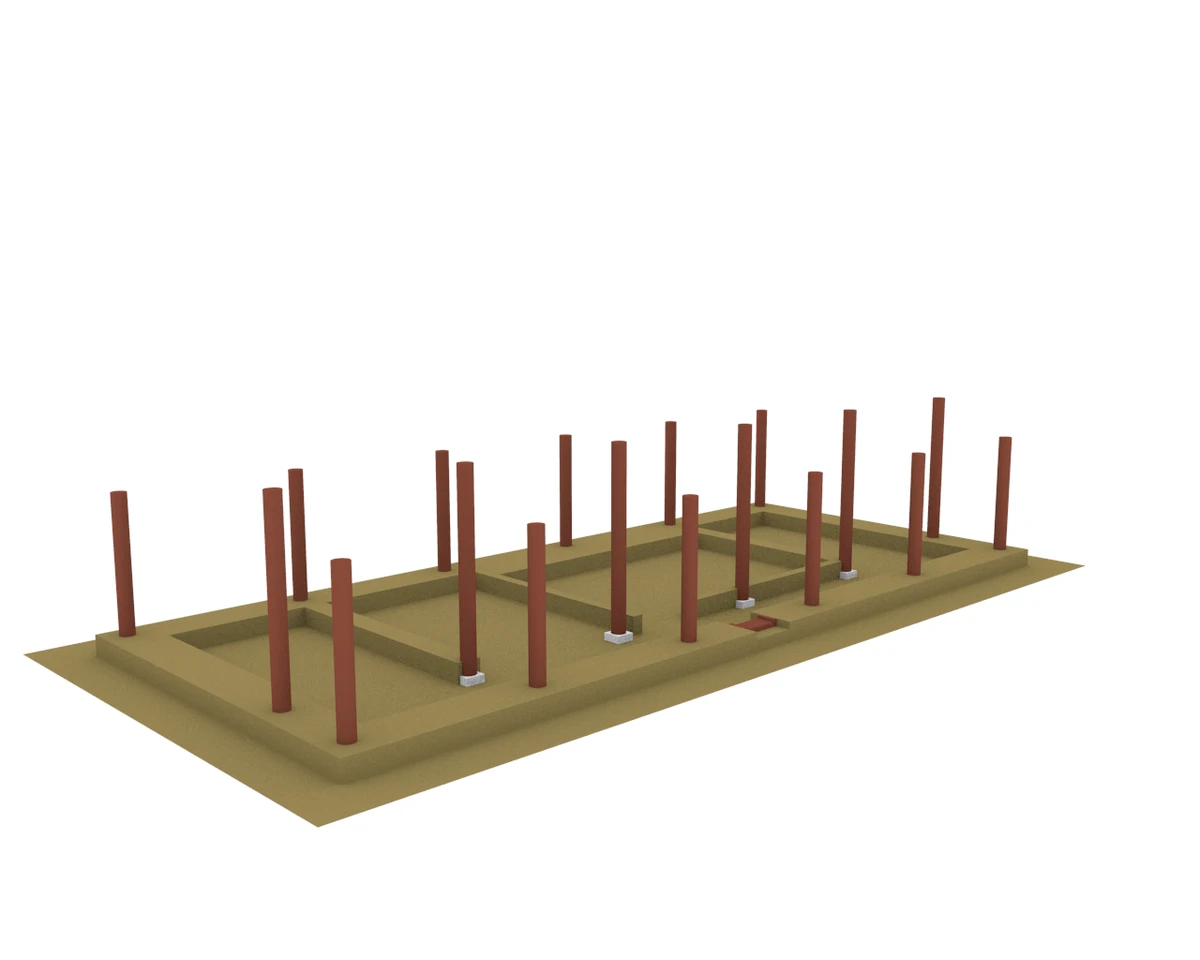

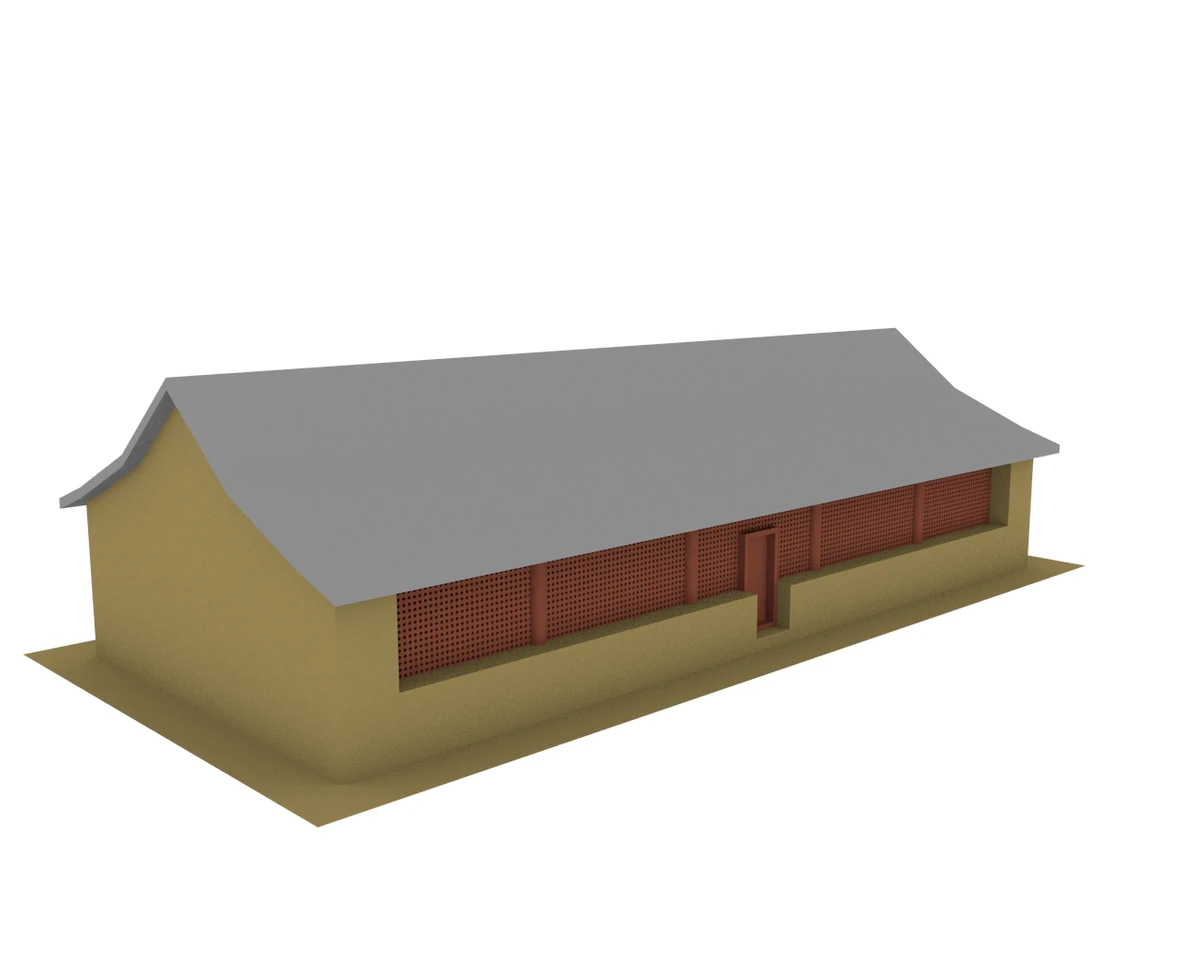

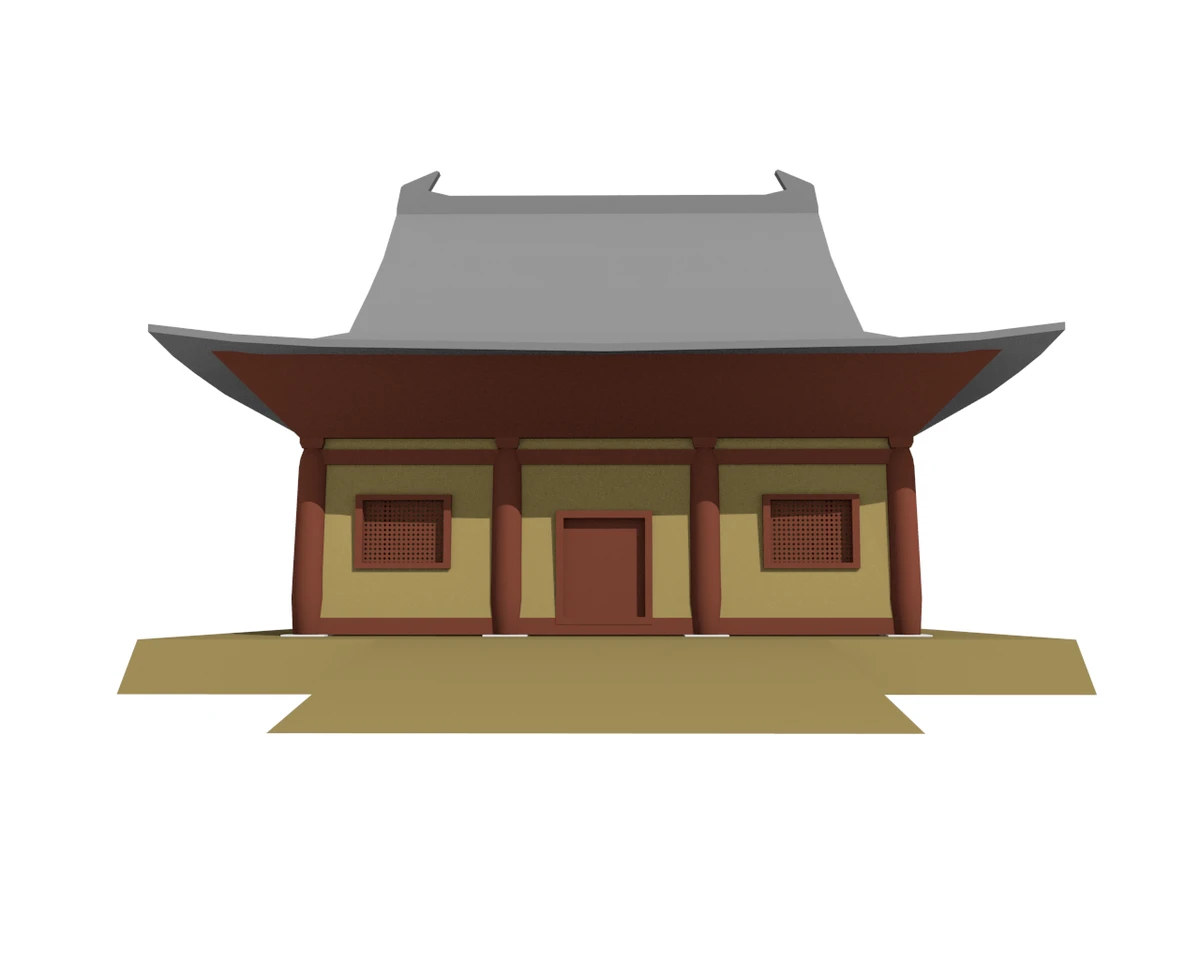

The northern outbuilding consisted of a wooden frame resting on simple stone slabs set into the ground. Elaborately designed column bases were not used for this small house. The wooden frame supported a roof made of fired roof tiles in the Chinese style. Although the tiles were unglazed, the roof was still richly decorated with sculptures. Along the lower edge of the roof, the eaves, alternating round discs with lion heads and sculpted borders were attached to the ends of the roof tiles. The alternation of these ornaments creates the impression of a garland running along the roof. In the layers of rubble inside the house, the excavation team also found two clay dragon heads among the remains of the roof, which were certainly also part of the roof decoration. Such richly decorated roofs originate from the Chinese building tradition and can still be seen on temples in East Asia and Mongolia today. Inside the building there were still some parallel timbers, which probably formed the support for a wooden floor. The house was divided into four rooms by narrow inner walls. The outer walls were made of unbaked clay bricks. At least in the base area, they were originally faced with hard, fired bricks. These protected the clay masonry from moisture and erosion. However, as in many parts of the ruins, there were hardly any remains of these high-quality bricks. It is likely that the entire ruined city was used for building materials in later times, when the Erdene Zuu monastery was built.

Reconstruction of the North House

Animal Sacrifice and Christian Worship – in One Building?

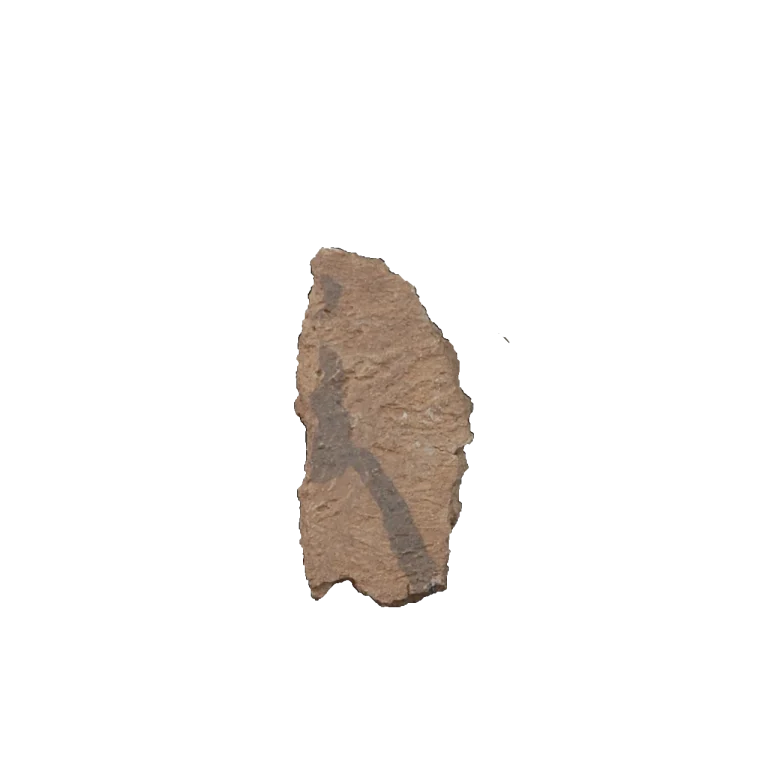

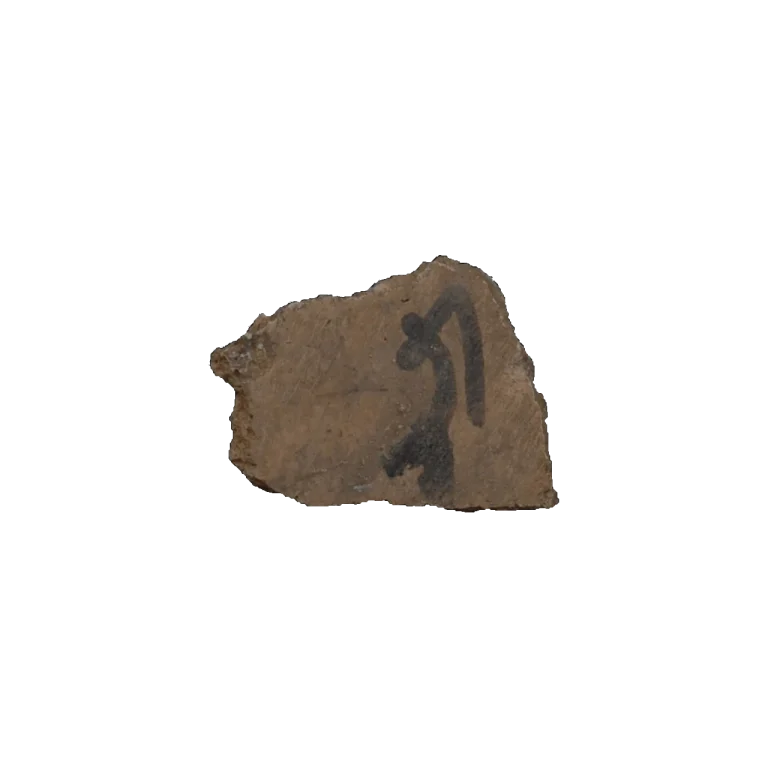

The remains of the northern house allow the building to be reconstructed as a typical outbuilding of a temple in the Chinese architectural style. But what purpose did it serve? Some exciting finds shed light on this. In each of the four rooms there were small brick plinths surrounded by ash and charcoal. These were probably small hearths on which something could be burned. However, this was not a residential building: there are no large quantities of waste such as pottery shards or the elaborate hot-air heating systems that were usually used in Karakorum to make the houses habitable in the cold Mongolian winter. However, the material found was of a completely different composition and very unusual: scattered throughout the interior of the house were horn cones, the bony insides of cattle horn. Although cattle horn was used in the Middle Ages as a raw material for all kinds of products such as combs, boxes, jewellery and similar small items, this is not the workshop of a craftsman. In addition to the horn cones, other finds such as defective tools, discarded semi-finished products or production waste would have been preserved in such a workshop. No, the horn cones were placed here for a different reason.

Avraga Balgas

Another settlement from the time of the Mongol Empire provides a possible clue. In Avaraga Balgas in the Khentij-Aimag of Mongolia there was a presumed camp site of Genghis Khan. After his death, it became an ancestral shrine where offerings were made to the deceased ruler. For example, meat offerings from sacrificial animals were deposited in pits around the sanctuary. The skull of an ox with its horns cut off was also discovered there. Preparations for similar offerings may have taken place in the outbuilding of the building complex in Karakorum.

Christianity and Nomadic Tribes

In all these regions, the sign of the cross can be found in the form of archaeological finds and on monuments. In the course of the Middle Ages, this form of Christianity also spread among some nomadic tribes in Central Asia, including the Naiman, Kerait and Merkit tribes, who later became part of the core of the rising Mongol Empire. Even some members of the Mongol dynasty were practising Christians, such as the influential Sorkhagtani Beki. She was the wife of Tolui, the youngest son of Genghis Khan and mother of Möngke, Kubilai (both successively Great Khans of the empire), Hülägü (conqueror of Baghdad and first Il-Khan of Persia) and Arigkbugha (Great Khan in competition with Kubilai). Not only did she succeed in placing her sons excellently in the power struggle within the empire’s elite, but in her prominent political position she also promoted religious tolerance within the Mongol Empire. Although she herself was a Christian, she also emerged as the founder of a Koranic school in Bukhara. With its spread throughout Iran, Central Asia, the Mongolian steppes and China, the Church of the East was probably the most widespread Christian church of the Middle Ages. So had the expedition in the north of Karakorum found the church mentioned in Rubruk’s report? Let’s take a look at the excavation of the main building.

The Main Building

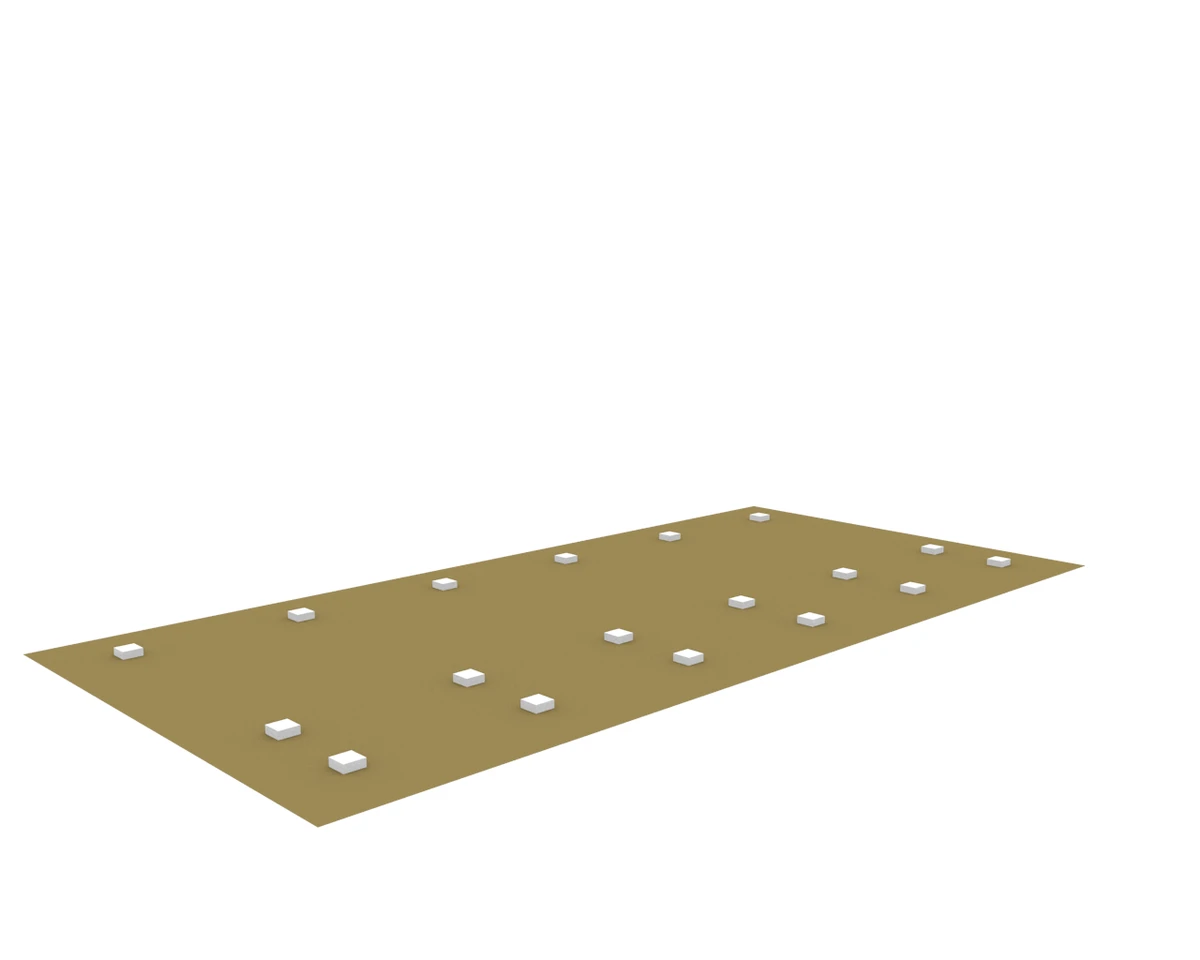

The main building to the east was already visible on the surface due to the size of its mound of rubble. When the archaeologists set about uncovering the structural remains, they found a large square platform about one meter high and 17.5 by 17.5 meters long. Originally there were 4 by 4, i.e. 16 rectangular granite column bases arranged on it. The rubble on and around the podium contained plenty of roof tiles as well as sculptural decoration of the eaves and the roof ridge. Here too, the ground plan and the building material clearly show the signature of Chinese planners and builders. Although only the podium, some column bases and the rubble of the roof were preserved, such that the building can be easily reconstructed from the remains. An interesting written source also helps: a Chinese building manual from the 12th century contains the rules and proportional measurements according to which temples, palaces and other public buildings were planned. Based on the height of the pedestal and the distance between the bases of the columns, the dimensions and proportions of the rising building were approximately reconstructed. According to the external shape, it was a small square temple hall, typical of smaller temples in China, where several examples of such temples from the Middle Ages have been preserved. The only unusual feature is the orientation with the entrance to the west. Could this be due to the building being used as a church? The purpose for which such halls were used in the Chinese tradition is not clear from the shape of the building. Halls of this type were used in China for Buddhist and Taoist temples, for palaces and residences and even for mosques. A use as a church is just as conceivable. We only have a few finds from this construction phase. Some fragments of sculptures resemble Buddhist sculpture, but no typological pictorial program can be reconstructed with certainty.

Reconstruction of the Main Building

Dating of the Building

Wooden remains of the construction were found in both building phases, which could be dated by analysing the carbon isotopes (14C) they contained. Despite the existing imprecision, it can be stated that the older building belongs to the first half of the 13th century and thus to the early period of the city of Karakorum. It probably also existed at the time of William of Rubruk’s visit. The younger building in the Chinese architectural tradition and the associated outbuildings were probably erected in the second half of the 13th century or at the beginning of the 14th century after the destruction of the older building.

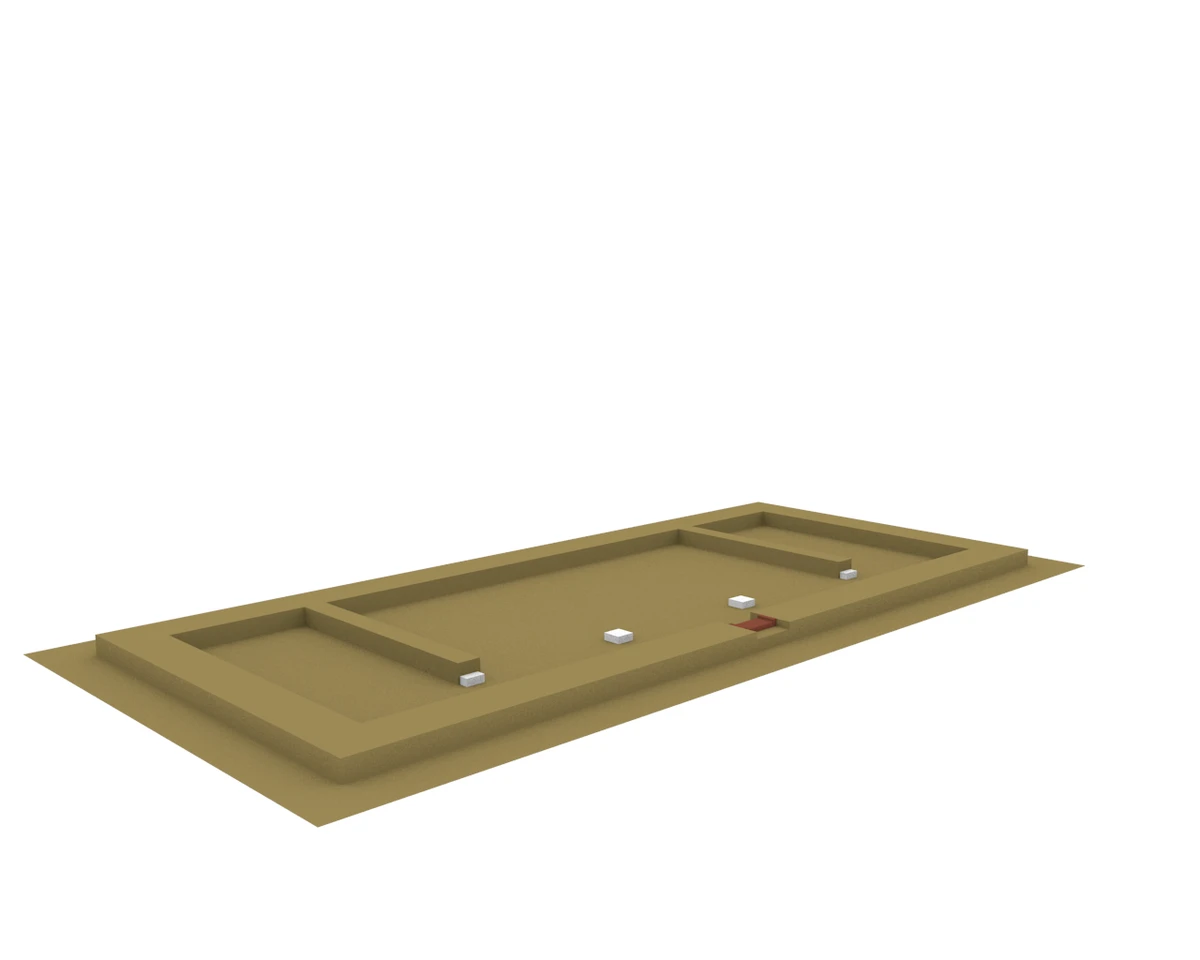

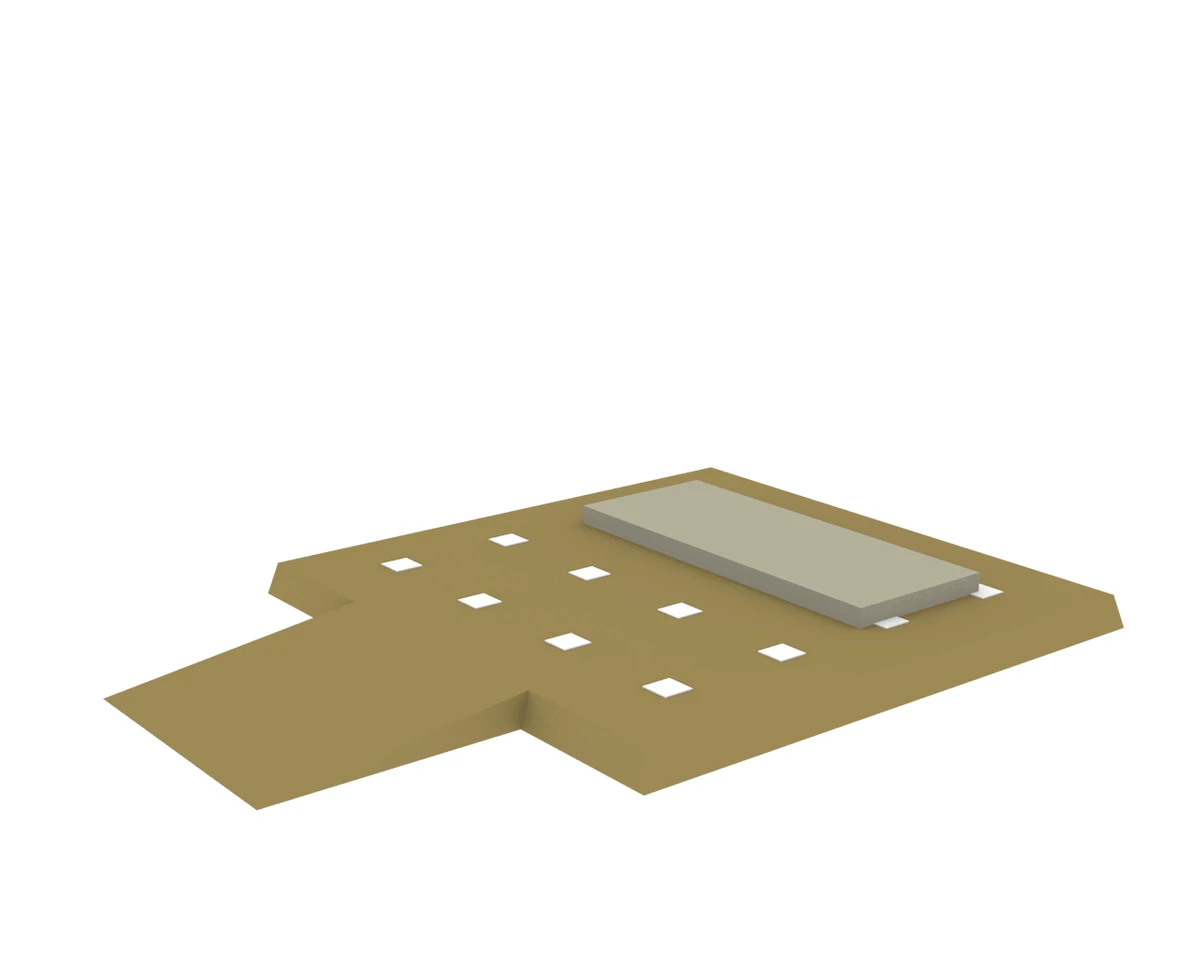

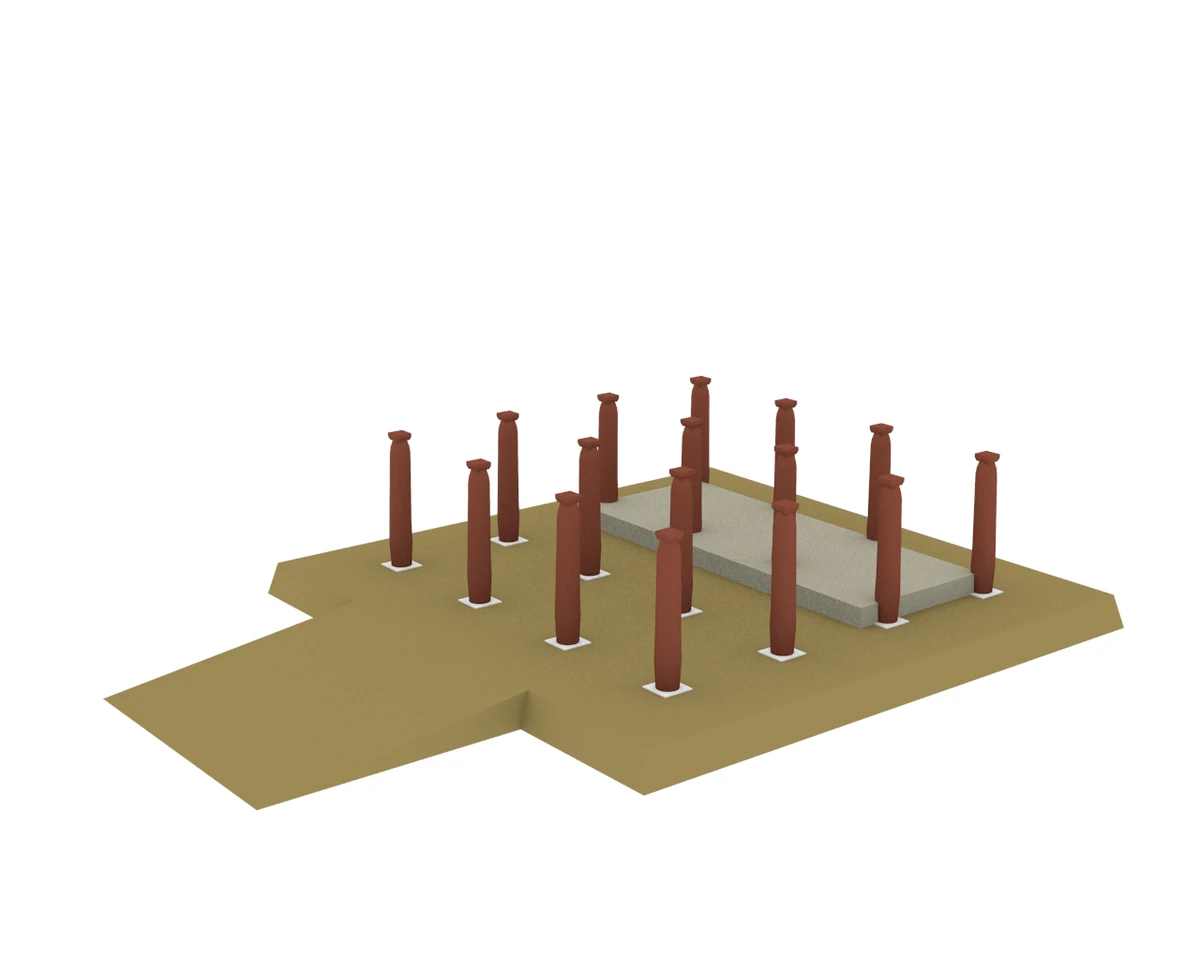

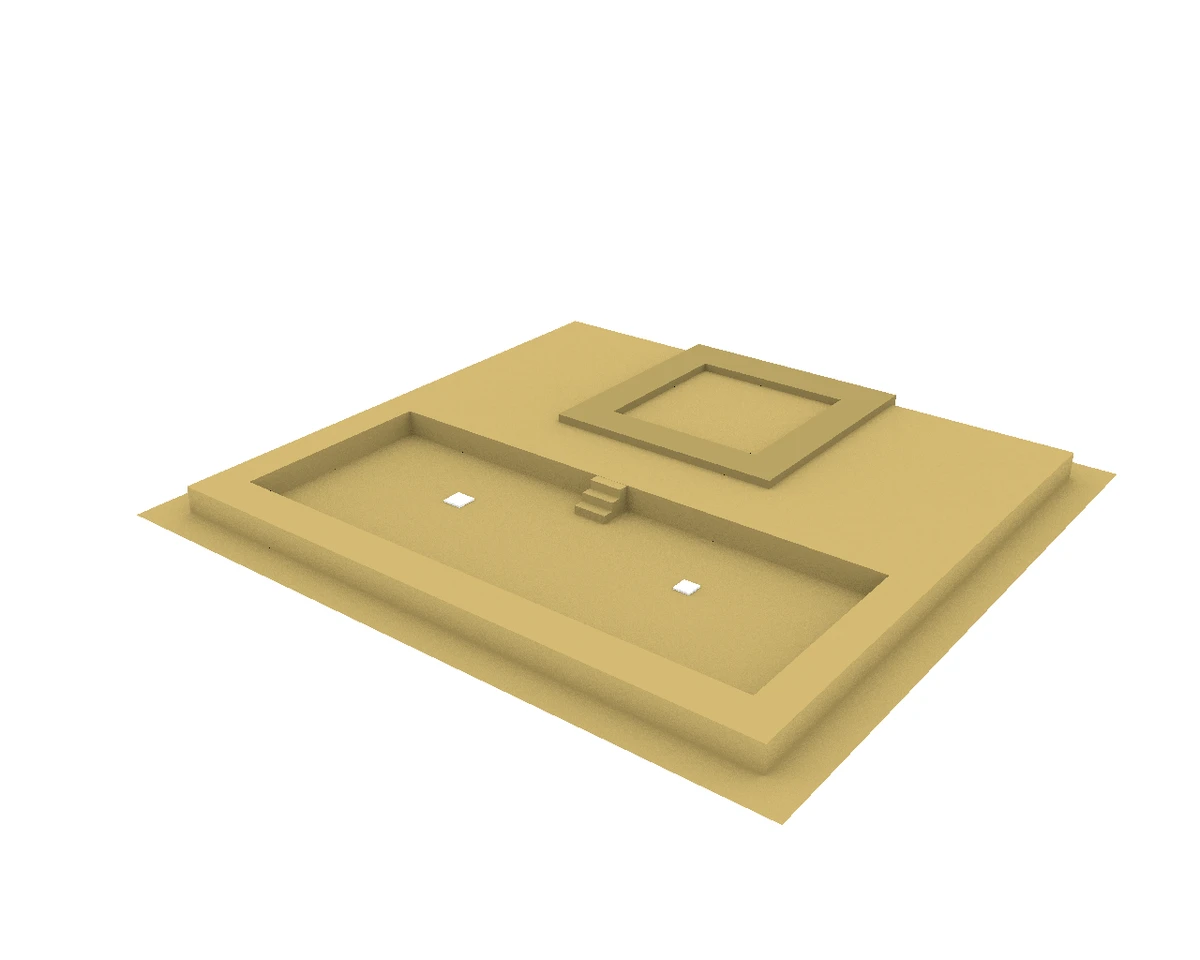

Central Asian Architecture

These structures bear witness to Central Asian architecture. The square foundation could have belonged to a domed building. Its interior was slightly raised by a small platform. To the west in front of it was a small three-aisled hall. This had a tiled roof supported by wooden pillars on column bases. The walls were made of unbaked mud bricks or rammed earth. The raised platform of the square building extended a little into the hall and formed a kind of small stage. This building was also oriented from west to east and seems to have followed the Christian custom. With the hall to the west and the structurally separated square, raised choir, the elevation of which extends into the assembly hall, the building actually resembles Central Asian church buildings of the Church of the East.

Reconstruction of the Older Construction Phase

Melting Pot of World Religions

The discovery of a possible church sheds an interesting light on the development of religious diversity in the multi-ethnic state of the Mongol Empire. How is it to be understood that the remains of an ancestral sacrifice cult with Christian liturgical equipment were found in a building here? Presumably, the close exchange between the Christian religion and indigenous customs gave rise to a very unique form of religious practice that combined the two. Chinese written sources also report on ancestor sacrifice cults, for example for the Sorkhagtani Beki mentioned above. Offerings were also made in honour of the ancestors in a Christian church or its outbuildings. The religiously diverse Mongol Empire thus produced forms of worship that combined elements of different religions and traditions. The different architectural traditions of the two building phases also bear witness to the political development of the empire. While the influence of Central Asian peoples in administration, politics and urban planning was evidently greater in its early phase, Chinese influence grew with Kubilai Khan’s accession to power – at least in the eastern parts of the empire. This development is also reflected in the buildings of the presumed church in the north of Karakorum. While the older building is clearly indebted to Central Asian forms, the younger one clearly shows Chinese architectural forms.